Newsletter Signup

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com

Did you know America’s first chocolate factory was right here in Dorchester, on the banks of the Neponset River?

It all started in 1764, when a young Irish immigrant and a local businessman struck up an unlikely partnership. John Hannon was an unemployed chocolatier, and James Baker owned a Dorchester general store. Baker sensed that Hannon’s unique skill set could be parlayed into a lucrative enterprise and offered to be Hannon’s financial backer in a chocolate-making venture.

The two men set up shop in a sawmill on the Neponset River between Dorchester and Milton. There, they began mass-producing chocolate by grinding cocoa beans between two enormous millstones to produce a thick, pure syrup. They sold their chocolate in “bricks” that could be mixed with boiling water to make a rich, unsweetened chocolate drink.

Business boomed, and in 1768, Baker and Hannon moved their operation to a bigger mill on the Neponset. But the partners’ relationship soured, and in 1771, Baker split from Hannon to open his own chocolate mill in Dorchester. The men became competitors, but by all accounts, both of their businesses continued to thrive.

John Hannon was an enigmatic character. Historians don’t know where he learned the chocolate trade, how he made his way from Ireland to Boston, or why he and Baker parted ways. In 1779, he embarked on a trip to the West Indies to buy cocoa beans and never returned. Some believe he died at sea; others speculate he staged his disappearance to escape a loveless marriage.

Regardless, James Baker was eager to buy up the chocolate mill that Hannon left behind when he vanished. After a legal battle with Hannon’s “widow,” Elizabeth Doe, Baker bought her out and in 1780 consolidated the two chocolate businesses into one. That year, he sold the first bars of officially branded “Baker’s Chocolate.”

Baker continued to manufacture chocolate until 1804, when he passed the business down to his son, Edmund. Savvy and ambitious, Edmund quickly built a brand new mill on the Neponset that produced cloth and grist, in addition to chocolate. Thanks to this diversification, he was able to weather the economic downturn of the War of 1812. In 1813, Edmund leveled the mill he’d just built to erect an even bigger mill complex on the same site. When the war ended in 1815, chocolate sales rebounded — the Baker family business was more profitable than ever.

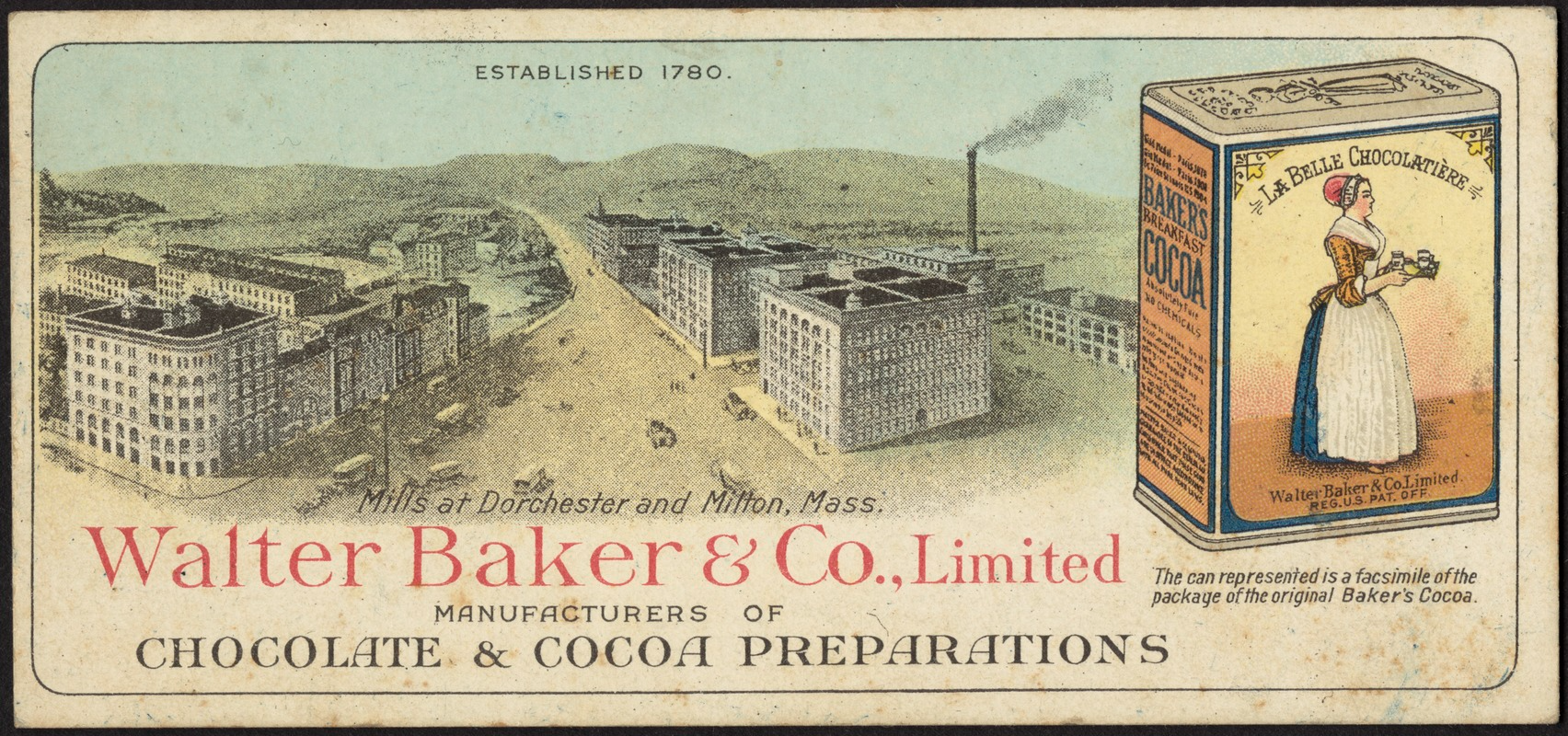

Edmund Baker’s eldest son, Walter, took over in 1823. He instituted important changes: officially naming the business Walter Baker and Company and introducing its first sweetened chocolates. (Up until 1849, Baker’s only sold unsweetened drinking chocolate.) Needless to say, the new, sweet chocolate bars were an instant hit. By 1835, the mill was producing more that 750 pounds of chocolate each day.

The business passed to Walter’s brother-in-law, Sidney Williams, in 1852. Walter’s step-nephew, Henry Pierce, took over two years later after Williams died suddenly. Pierce ran the company from 1854 to 1895, concurrently with terms as the mayor of Boston (1872-1873 and 1878-1879) and a U.S. congressman (1873-1877). Under his keen leadership, the chocolate factory would achieve local dominance and international renown.

First, Pierce bought out the two competing Dorchester chocolate producers — the Preston Mill and the Webb Mill — effectively eliminating the local competition. He added more buildings to the already-impressive Baker mill complex on the Neponset and ramped up production. Perhaps most importantly, he brought Baker’s chocolate to a series of world’s fairs and expositions beginning in the 1860s. When the chocolate won a Silver Medal at the 1867 Paris Exposition, it propelled the brand to a new level of notoriety.

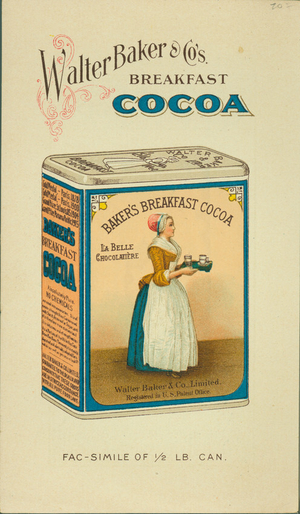

Pierce had a knack for marketing and in 1877 introduced “La Belle Chocolatière” (the beautiful chocolate girl) as the company’s apron-clad, porcelain-cheeked mascot.

In the coming decades, La Belle would become synonymous with Baker’s chocolate as her image proliferated across the company’s packaging, advertisements, and branded recipe books. Baker’s even hired women to dress up in bonnets and aprons to host cooking classes and give tours of the factory.

In 1895, Pierce incorporated the company as Walter Baker and Company, Ltd, capping off 115 years of family ownership. According to the book “Sweet History: Dorchester and the Chocolate Factory,” Pierce said of the transition: “The die is cast. Walter Baker & Company [is] now a corporate body. They say corporations have no souls, but they outlive men, and I have done what I think is best for the business and for everyone.”

Walter Baker & Company was acquired by General Foods in 1927 and moved from Dorchester to Dover, Delaware, in 1965. General Foods, in turn, became part of Philip Morris Companies — now Kraft Foods — in 1985. These days, Kraft manufactures Baker’s Chocolate in Quebec. Though the company is no longer locally owned, La Belle Chocolatière’s silhouette is still featured on its packaging, a nod to its Dorchester roots.

Even after the chocolate factory moved away, its stately brick buildings remained as fixtures of Dorchester’s Lower Mills District. In 2010, after three decades of redevelopment, they reopened to the public as the Baker Chocolate Factory Apartments. The architects took care to preserve the buildings’ history and even discovered a painting of La Belle Chocolatière hidden under plywood during the renovation. It’s now on display in the apartment complex’s gallery space, reminding residents of the more than 250 years of chocolate-making history beneath their feet.

To learn more about the history of chocolate manufacturing in Dorchester, check out “Sweet History: Dorchester and the Chocolate Factory” published by the Bostonian Society.

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com