📚 Stay up-to-date on the Book Club

Catch up on the latest Boston.com Book Club pick and join the virtual author discussions.

Isabella Stewart Gardner spent years of her life chasing beauty in all its forms. The 19th century art collector is known today for being the Fenway museum that bears her name, and she was as much a force in her day as she is now.

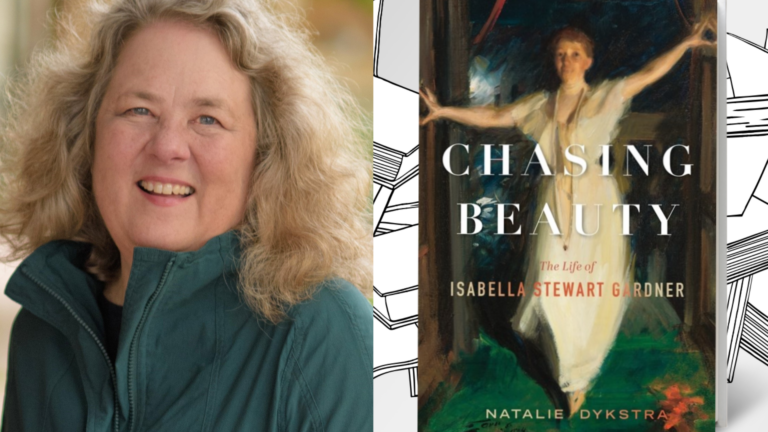

Natalie Dykstra, award-winning writer and researcher, had long been a fan of the museum and of the woman behind it. She felt it was time the public loved her story, too. She joined us to discuss the eccentric socialite for our latest Book Club discussion.

“I was fascinated by her eponymous museum, which is on the Fenway here in Boston … but it seemed to me that there hadn’t really been a story, a big story, told about her and particularly the earlier parts of her life,” she said.

It’s a life that was marked by as much tragedy as it was privilege. Isabella Stewart was born to a wealthy New York family and later married Boston Brahmin Jack Gardner. After moving to Boston, Gardner suffered the loss of multiple family members in the span of one year, including her only child.

In the face of that heartbreak, she turned to art and travel, creating a collection that rivaled some of the nation’s best museums. Today that collection is on display for the public to see, thanks to Gardners’ commitment to eschewing the gender roles of her time and forging a reputation as a respected tastemaker and business woman.

“The museum is also an expression of her personality … It’s also a kind of record of her thinking, her ambition, her values for taste. And so it becomes a biographical document you can read for evidence, even though of course, it’s an astonishing art collection and a museum in another register,” she said.

At our latest virtual author discussion, Dykstra was joined by Lauren Tiedemann, owner and manager of the Winchester bookstore Book Ends to discuss the new book, Gardners’ travels, and how she built a lasting legacy.

Read on for takeaways from their discussion, watch the full recording below, and sign up for more Book Club updates.

It may surprise you to know that Isabella Stewart Gardner didn’t open her museum until she was 63, well into a long life for a woman of her generation. Dykstra was struck by how much of a presence the museum has become in Boston’s Fenway in spite of few Bostonians knowing much about the early life of its namesake. She said she wrote the book to shed some light on that story, and satisfy some of her own curiosity as well.

“I got very attracted to the shape of her life,” the author said. “I wondered if I could, if it was possible to tell a biographical story using Isabella’s collection, her paintings, the objects that she put in a room. And because she stipulated in the will that nothing could ever be changed, it’s a record of her intent.”

Much has been written about how Isabella Stewart came to marry her husband, Jack Gardner, and move to Boston, where she would eventually open her museum. But Dykstra said she was interested in uncovering more about her early life in New York and the final chapters of her life after she’d realized her vision of sharing her art collection with the world.

She did that by diving deep into primary sources from Gardner’s life and turning to secondary sources. Equally important as the research, is the writing of the biography. She said the writing process teaches her what she hadn’t already uncovered in the research.

“I could see her develop, watch her develop through those chapters,” she said. “Voice is everything in biography. You want to have a writing voice that feels of the time.”

Dykstra shared a passage from the book detailing Boston’s excitement at Gardner’s purchase of a Botticelli painting — the first to be displayed in the city. Gardner and her contemporaries were a key part in elevating the city’s cultural reputation in the arts, according to the author.

“You get a sense [that] Boston is competing always with New York. And of course it’s much smaller, and competes in the musical circles, art circles, libraries, universities, right. And so there was this feeling that it was putting Boston on the map in terms of an important American collection,” Dykstra shared.

She was close friends with young curators at the Museum of Fine Arts, but also competed to build great collections within the city.

“As her collection grew, and as word got out of the masterpieces that she was starting to collect, people started to really appreciate that now Bostonians were going to be able to firsthand see these paintings. I think in our image-saturated age, it’s hard to get back to a time when it was hard to see art,” she said.

Gardner suffered a string of losses shortly after her marriage, including the death of her son, niece, and nephew, as well as a miscarriage. There are a lot of personal letters from that time in her life as she kept in close touch with her brother and sister-in-law.

“I remember that I knew that that was a pivot. I mean, it changed her utterly. Of course, you don’t go through what she went through that year, and not be changed by it,” she said, adding that Gardner was only 26 at the time of her miscarriage and learned she would never be able to have children again.

After that, Gardner had to grapple with what her life’s passion would be after that loss. Going overseas to get some distance from that heartbreak helps spark a new life and a deepened interest in art.

“I didn’t make a one to one correspondence between loss and museum because it’s more complicated than that. But is that a red thread that runs all the way through the story? It absolutely is,” Dykstra said.

An important inspiration for Gardner were her travels in Europe, where she met influential artists and other tastemakers. In writing the book, Dykstra traveled to the cities that shaped the art collector, including Florence, Milan, and Venice. She tracked Gardners’ travel albums, letters to loved ones, photographs, and diary entries. While in those cities, she retraced Gardners’ steps, staying at the same hotels when possible and even attending art auctions that Gardner would have frequented.

“She kept 28 travel albums in all and they’re meticulously put together and so you can track by date and place. [They were] often filled with photographs. There’s a few that are filled with diary entries, but most are visual records of what she had seen. And so I would track her through Florence and I would try to replicate her travels through Florence,” she said.

The final painting of Gardner was done by John Singer Sargent in the space of a single morning, according to the researcher. In the portrait, Gardner is in her twilight years but Dykstra believes the artist captured the vibrancy of her younger self with the inclusion of a shadow of a young woman to the subject’s left. While she was unable to find a Sargent scholar to confirm this was done purposefully, the author said she believes it was.

“It seemed intentional. And what was he trying to tell us with that dual portrait of her in her old age and her in her youth? I think it had to do with this extraordinary vitality that she had all through her life,” Dykstra said.

Catch up on the latest Boston.com Book Club pick and join the virtual author discussions.

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Be civil. Be kind.

Read our full community guidelines.