Newsletter Signup

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com

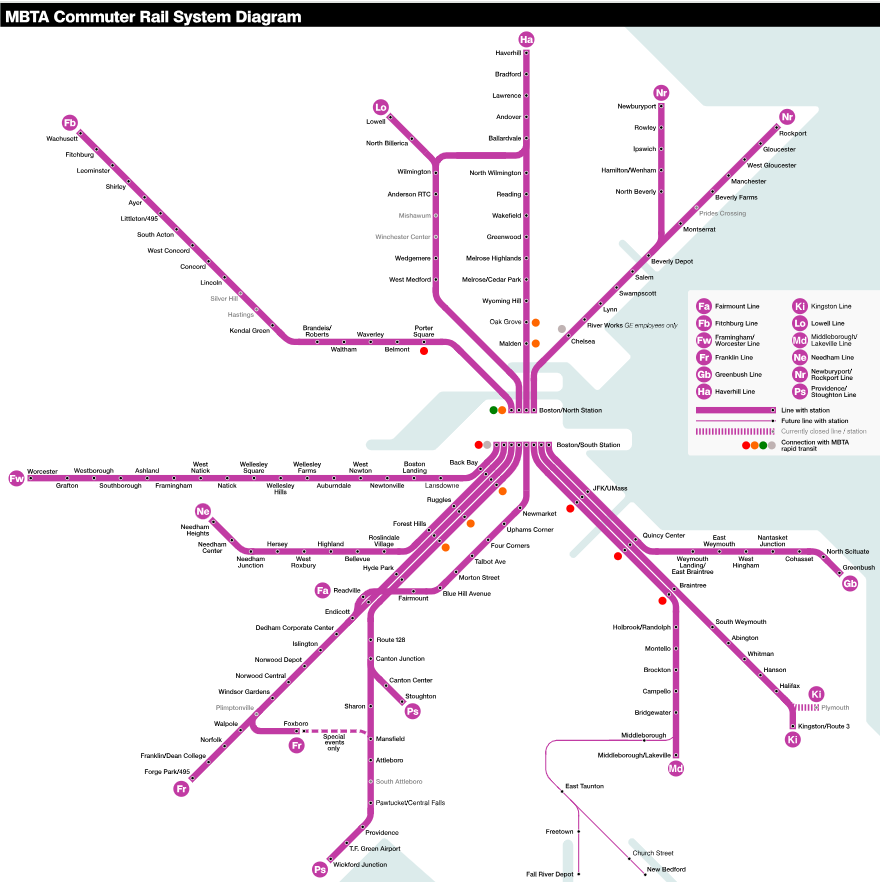

Practically speaking, Boston’s commuter rail system is actually two separate systems. One extends from South Station down the Worcester, Needham, Fairmount, Franklin, Providence/Stoughton, Middleborough/Lakeville, Kingston, and Greenbush lines. The other stretches from North Station along the Fitchburg, Lowell, Haverhill, and Newburyport/Rockport lines.

Amtrak service through Boston is similarly bifurcated: Trains running north to Portland, Maine, depart from North Station, while South Station is Boston’s gateway to Providence, New Haven, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C.

To traverse the 1-mile distance between the two stations, commuters must walk 25 minutes or take a 15-20 minute subway trip on two different lines (the Red Line and the Green or Orange Line).

The North-South Rail Link — a 2.8-mile tunnel connecting North and South stations — would bridge the north/south divide, allowing trains to run interrupted across the region. Advocates say the benefits are clear: Building the link would facilitate faster commutes into the city from farther away, easing pressure on Boston’s choked housing market and taking cars off congested highways. Better regional transit is good for economic growth, they say, and for the climate.

So why has this seemingly simple fix never quite gained traction? Depending who you ask, it’s a testament to the eye-popping price tag, Boston’s Big Dig hangover, or a deeper aversion to big, ambitious projects.

Massachusetts lawmakers have been talking about building the NSRL since at least the administration of Gov. Michael Dukakis in the 1970s. Congress even voted to fund the Rail Link’s construction in 1987, as part of an $87.5 billion highway and mass transit bill — which also included money for the Big Dig and over 100 other projects around the country. But President Ronald Reagan vetoed the bill, spurring a tooth-and-nail fight in the Senate to override the veto and save the legislation. In the course of that battle, the Rail Link project was sacrificed to appease the 13 Republican senators who broke ranks with Reagan and voted to override.

Since the ’80s, successive generations of national, state, and local elected officials have thrown their support behind the NSRL. Congressman Seth Moulton is a particularly staunch advocate; former governors Dukakis and Bill Weld, Sen. Ed Markey, and Mayor Michelle Wu are also supporters, along with a laundry list of state senators and representatives.

But building another tunnel beneath downtown Boston would be complicated and expensive. In 2017 a Harvard Kennedy School cost analysis estimated the Rail Link would cost between $3.8 and $5.9 billion in 2025 dollars. The price range reflected different build options: two versus four tracks, different routes beneath the city.

The year after the Harvard study came out, Gov. Charlie Baker’s administration released it own “feasibility study.” This time, the Rail Link was estimated to cost a hair-raising $12.3 to $21.4 billion. (For reference, the infamous Big Dig ended up costing about $24 billion.)

Which estimate is most accurate? And how would the benefits of this major transit project measure up to its costs? Ever since Maura Healey replaced Baker in 2023, proponents of the North-South Rail Link have been asking these questions with renewed urgency.

In response to questions from Boston.com, a spokesperson for the state Department of Transportation said that “currently there is no new study planned regarding creating passenger rail service between South Station and North Station in Boston.”

But supporters of the project are lobbying the Healey administration to reexamine the 2018 feasibility study and recognize their vision for the Rail Link.

Moulton, who represents Massachusetts’ 6th District, has been pushing for the North-South Rail Link for years. In a statement to Boston.com, he stressed the need for bold changes to Massachusetts’ transit landscape.

“We say people should use transit, but we only invest in our highways and airports,” Moulton wrote to Boston.com. “I don’t buy the argument that fixing our rail network is too hard or too expensive. If we make smart, transformative investments like North-South Rail, they will pay for themselves in economic benefits many times over.”

Today, the disconnected transit system limits where people can live and work within Greater Boston. According to Moulton, the Rail Link would enable you to “travel straight from Salem to Providence, or Worcester to Maine, and the jobs and housing opportunities that open up will be extraordinary.”

One of the key promises of the Rail Link is that it would create stronger links between Boston and smaller satellite economies like Chelsea, Everett, Lynn, and Salem. The Rail Link could also open up prime real estate in downtown Boston that’s currently occupied by Amtrak and commuter rail train yards. If North and South Station’s “stub ends” were linked, those yards could be moved outside the city.

Jarred Johnson is the executive director of TransitMatters, a nonprofit that advocates for better public transportation in Greater Boston. The way he sees it, the question of whether to invest in improved public transit is an existential one for Boston.

“Other places will eat our lunch,” he said, pointing to cities like Toronto, Montreal, and New York, where major transit expansions are either planned or already underway. “A city where the trains are slow, and where they’re not expanding to meet demand — that’s a city that falls behind.”

Johnson pointed out that the 2018 feasibility study only looked at costs — not benefits or value created.

“Let’s be honest, the last governor had no intention to ever do the project,” he said. “We need a study that actually presupposes that we think this is a good idea.”

Remember that Harvard Kennedy School study that estimated the North-South Rail Link would cost at most $5.9 billion, not $21 billion? It was directed by Linda Bilmes, a leading expert on public finance who serves on the United Nations Committee of Experts on Public Administration. Bilmes and her graduate students used Federal Transit Administration data to estimate the cost of each component of the Rail Link. They double-checked the result against cost estimates for comparable tunnel projects in other countries, then triple-checked it using a Monte Carlo analysis, a mathematical model that accounts for uncertainty.

“We have pretty good confidence that we have got the right order of magnitude amount because of the way that we did the study,” Bilmes told Boston.com.

Since 2017, high inflation has raised the expected costs of the tunnel. The study also didn’t account for the cost of electrification. Together, Bilmes estimates those factors could add about $2 billion onto her original estimate, raising the price tag to about $8 billion.

That’s still significantly lower than the 2018 Baker-commissioned study’s low-end estimate of $12.3 billion.

Plus, Bilmes said, “We weren’t asked to look at the benefits. … If I were going to do a cost-benefit study, I’d be delighted, because the benefits are enormous.”

Over 20 years, the economic benefits of opening up North/South travel through Greater Boston for business, recreation, and touristic purposes would “more than pay for the cost of the tunnel, many times,” Bilmes said.

In the short term, though, the MBTA has no budget for capital projects. So state lawmakers have set their sights on a less ambitious plan to relieve congestion on the commuter rail: an expansion of South Station.

The South Station Expansion would add 10 new train tracks (alongside the current 13) and a new bus terminal to the downtown transit hub at an estimated cost of $4.7 billion. The plan involves purchasing and redeveloping the adjoining U.S. Post Office site to make space for the new tracks.

“MassDOT considers this a priority project as South Station is currently at capacity,” a DOT spokesperson told Boston.com.

But the South Station Expansion wouldn’t address the fundamental problem of the north/south divide across Boston’s rail network. Moulton and Johnson both see it as a band-aid solution.

“The best way to expand capacity at South Station is to build the North-South Rail Link,” Moulton said.

Johnson added: “When I think about South Station Expansion and how expensive that is … and contemplate building tracks all the way up to the [Fort Point] channel, that to me is a wasted opportunity and a waste of money,” considering that land is “some of the most valuable real estate on Earth.”

Congressman Moulton expressed optimism that the Healey administration is taking a forward-looking view of the state’s public transportation.

“My team and I are in a continuous dialogue with the Healey Administration, from the Governor and Secretary of Transportation on down, and we are pleased to see an administration finally taking the future of transportation seriously,” he wrote to Boston.com.

Johnson called for a new feasibility study and an updated cost estimate for the North-South Rail Link. He also urged the Department of Transportation to consider the Rail Link as an alternative to the South Station Expansion.

Bilmes and her team at Harvard are working on a cost-benefit analysis comparing the two projects. Results will come out later this year.

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com